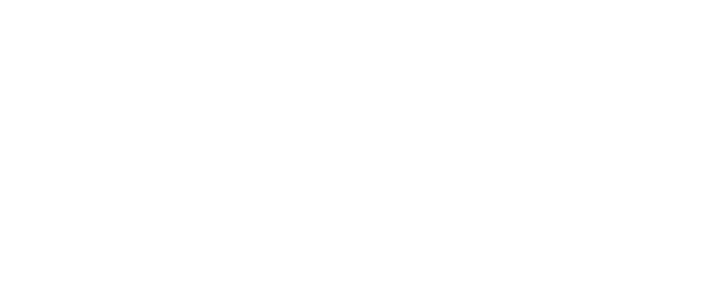

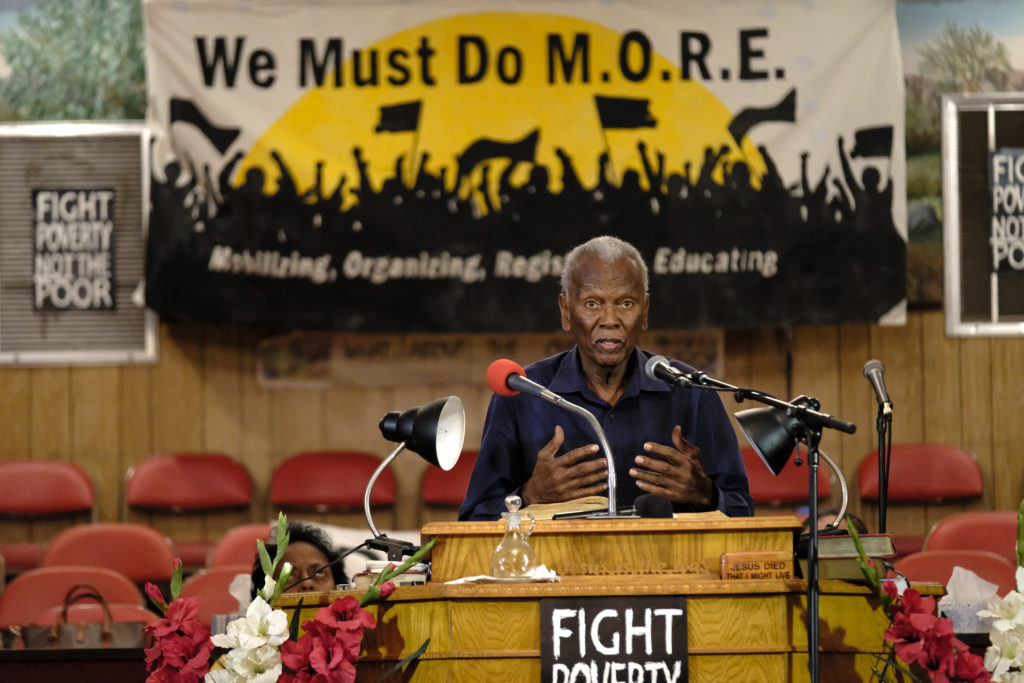

Robert Taylor, Concerned Citizens of St. John’s Parish, Louisiana

Robert Taylor grew up in a ‘remnant of the old plantation system,’ in the town of Reserve in St. John’s Parish, Louisiana, one of the many majority-Black river communities between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. This area has come to be known as ‘Cancer Alley,’ due to the rates of cancer there that have reached 1,500 times the national average — a result of the growing petrochemical industry. Robert, now 80 years old, founded the Concerned Citizens of St. John Parish in 2016, and is fighting for his family members, friends, community and the generations to come.

I was born into the plantation life in 1940. We’re in the southeast in a section of Louisiana between New Orleans and Baton Rouge and our communities are river communities, they all border the Mississippi River, they’re what’s called river parishes. This area was primarily agrarian, it was sugarcane plantations. My father and my mother worked at the sugar refinery.

My mom’s sister had nine kids. As they got to be 10 years and older, the kids, they started doing what their mother did, they’re in the sugar cane field cutting sugar cane. The fact that my dad was actually fortunate enough to get a job working in the sugar refinery itself gave us a somewhat better life.

I grew up and I was able to go to school and I developed friends. I never had to actually work in the sugar cane field. I was in the building trades and I eventually became a general contractor so I was able to build a home for myself and my family.

The majority of the communities between New Orleans and Baton Rouge were plantations — it was in the late 40s, early 50s that that began to change — In the late 40s, early 50s, the petrochemical industry began making inroads, buying out the sugar plantations, and it eventually changed from agrarian to industrial.

When they bought out the plantations they left thousands of people still there on the periphery; the little communities that we have, we’re the descendants of those folks.

Our community is now the remnants of that old plantation life.

When they bought out the plantations they left thousands of people still there on the periphery; the little communities that we have, we’re the descendants of those folks … Our community is now the remnants of that old plantation life.

Between Baton Rouge and New Orleans we have 60 miles of chemical plants dumping poisonous chemicals of all sorts into the Mississippi River, into our aquifers and into the air. By the time the river gets to St. John’s Parish it is something that you should be afraid to even put your hand in. But that is where we get our drinking water.

We weren’t prepared for industry. We are really not employed by it. It brought no benefits to us. It’s mostly poor, uneducated black folk in our communities — the average annual income in St. John’s Parish is $17,000.

Some of us found work, and we had to develop crafts, you know we did what we could in order to survive. But when the petrochemical industry came in, life became different for us. Drastically. We didn’t realize the impact that the industry was actually having on us.

I was 25 when I built my home with help from a loan from the Department of Agriculture — the Farmers Home Administration. It was what was called a poor people’s housing development which enabled me to be able to acquire a home and to be able to improve on it. It was a 900 square foot home. It was very modest. Since I was in the construction business I was able to convert that 900 square ft home into a 5000 square foot home, which was unusual.

You know we got the big home that we built that I thought was going to be there for my children and my grandchildren. I made an investment there that I thought was gonna be generational, but DuPont changed that drastically.

We moved in after we had our last child in 1968, we had four children — two boys and two girls. So you know it was ideal — the girls had their bedroom and the boys theirs. That same year Dupont went into business in our Parish, less than a half mile from my house, and began dumping chloroprene along with 28 other chemicals into our environment. So that child was exposed to it from birth. She’s the one that has been mostly impacted — she’s debilitated, she has an autoimmune disease that makes her vulnerable to any kind of opportunistic diseases.

When that materialized in her forties, she was a working nurse, but now she’s incapacitated. She can no longer work. She’s on all of these horrible medicines trying to fight off the effects. We had to move her out of here once we realized that’s what caused her the illness. It was too late. It was a lifetime of exposure that got her to where she was. My wife had survived cancer and other debilitating diseases so I wound up having to move her out of here too.

By the late 1960s and 70s, the majority of white people that were living there right along the river (we live in the back across the track), were aware of what was happening with Dupont so they they moved out to a safer, more distant area north of the Airline Highway, called NOAH. All of the Parish investment went to developing NOAH.

By the 80s people began to suspect that the plant had something to do with the rising rates of cancer and the respiratory and other cardiovascular diseases that we were suffering from. But it was mainly black people who were suffering these diseases so not much was done about it.

By the 80s people began to suspect that the plant had something to do with the rising rates of cancer and the respiratory and other cardiovascular diseases that we were suffering from. But it was mainly black people who were suffering these diseases so not much was done about it.

I’m sure the medical profession had to notice it but a number of things were working against the poor black folks, many did not have insurance so when they did get sick they couldn’t get treatment, there was no prevention. There was nothing in terms of preventive policies or protocols in place. People who were suffering got treated in an emergency room.

It wasn’t until 2016 that attention was brought to this. Early that year I came home from work to find my wife really in such a bad way and I noticed how strong that chemical odor was so I called 911. The emergencies came out and the fire chief got out of his car and he was struck by the odor. His statement to me was, ‘My God I don’t know how they expect you people to live like this.’

He said, ‘well, you can call and report ’em but you know that plant is one of the largest taxpayers in the Parish so I don’t know how much luck you’re going to have with that.’ And he was absolutely correct.

The Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality was just a front for the petrochemical industry. So in 2016 EPA decided to take action since nobody locally was doing anything. The EPA set up a monitoring system where they monitored the level of chloroprene, setting the the level at which humans could tolerate a lifetime exposure at 0.2. After 4 months they told us there was no place inside St.John’s Parish that had a safe level of chloroprene.

He said, ‘well, you can call and report ’em but you know that plant is one of the largest taxpayers in the Parish so I don’t know how much luck you’re going to have with that.’ And he was absolutely correct … The Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality was just a front for the petrochemical industry.

Our state agency on the other hand said that our cancer rate was the same as the national rate, which was 0.9 percent. The EPA came in and did a study and showed that the people who lived in Reserve, my community within St. John’s Parish, were at 1,500 times the national average in cancer risk.

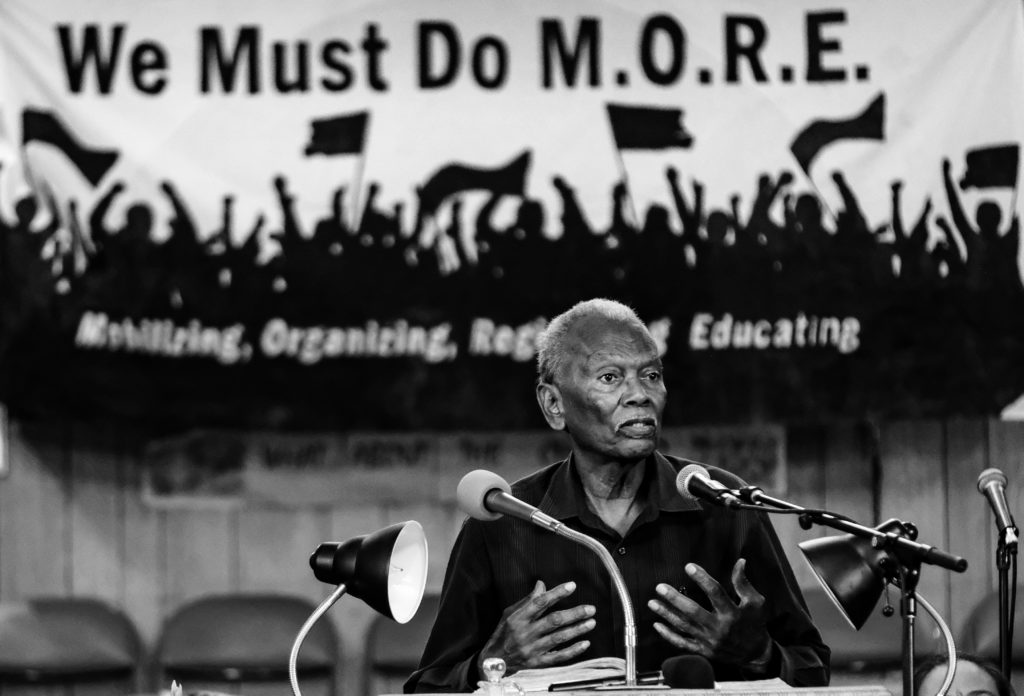

When we found out from the EPA how badly we were being poisoned by the chemical plants we went to our government seeking help. What was highly motivating for us was the elementary school that was only 1,500 feet from that plant. Still today four to five hundred black elementary school children go to school there, where the EPA measured concentrations of chloroprene at four to seven hundred times what they considered a safe level. That is a gas chamber these children are sitting in.

From the outset we asked that the plant just not poison us, that they adhere to the EPA regulations. But our government has abandoned us totally. We have been designated a ‘sacrifice zone.’ That is ungodly. I cannot believe in the 21st century, in a so-called Christian country, that they decided that black people can be sacrificed for the profit of corporations.

We have been designated a ‘sacrifice zone.’ That is ungodly. I cannot believe in the 21st century, in a so-called Christian country, that they decided that black people can be sacrificed for the profit of corporations.

Our only hope now is to reach out to the U.N. We need to bring our plight to the world because obviously this country has already written us off if they have designated us a sacrifice zone. It is clear to me that a genocide is being perpetrated against the black people of Cancer Alley. Because 92% of the population that is impacted by the petrochemical industry is black in a state where we’re only at 32% of the population.

I’m keeping up this fight because that’s where my whole life is. That’s where all my friends and relatives are. I just cannot give up the fight as yet to try to make life there livable for our people.

And obviously the obstacle seems to get greater as I get more involved in this because now I’ve got to find out who is playing God and deciding to sacrifice me and my family and friends at the feet of the petrochemical industry for the benefit of the profit of these majority of foreign corporations.